In my life I've made an attempt to reconcile my studies and knowledge of science with other facets of my life that are no less potent, nor less important to my mind. Though there are clear conflicts between some of my scientific and spiritual ideas, there are areas of overlap and agreement. The same can be said even within the various truths of my political repertoire. For instance, universal healthcare is appealing, as is a balanced federal budget. There is conflict, dissonance here, but there can be resolution.

One of the lessons I took home from the Tao te Ching is that we can learn from, and can best experience peace, fulfillment and productivity in our lives by learning the patterns and ways of nature. As stated in the translation linked above:

Man follows the earth.In Herman Hesse's Siddhartha (full text), the title character, toward the end of his life and spiritual journey, lives with a ferryman by a river. At one point in the narrative, Vasudeva tells Siddhartha to learn from the river.

Earth follows the universe.

The universe follows the Tao.

The Tao follows only itself.

The river has taught me to listen; you will learn from it, too. The river knows everything; one can learn everything from it.Nature (earth, the river) is the ultimate teacher and master for us mortal folk, in that the pattern of the universe is written in the pattern of earth. Hermeticism uses the phrase As above, so below. The Lord's prayer: On earth as it is in heaven. The microcosm reflects the macrocosm. By learning and applying the patterns of the earth, we humans, if we but humble ourselves, may come closer to an understanding of the universe, the heavens, the infinite, etc.

In the West, our scientific method has evolved out of the careful study of this nature (as has science elsewhere . . . I'm a little more familiar with the evolution of Western science) . . . the revolution of cosmic spheres, the ebb and flow of the tides, the movement of air masses, the cycles of our seasons, the dance of excited particles in the auroras. Our modern studies of physics, astronomy, chemistry and biology were once lumped under the umbrella of Natural Philosophy.

If I tried to explain what scientists do to a kindergartener, I suppose I would say that we ask nature (or, the universe) questions. I suppose I would give the same answer if I were asked what a Taoist does.

To me, engineers operating in the arena of biomimicry embrace this ideal in its fullest. The idea is simple . . . let natural systems provide inspiration for technological advance. Let's learn from someone who's been doing it longer and more efficiently. We now have artificial gecko feet for climbing walls. Aerospace engineers are taking a cue from maple seeds in the design of small aerial vehicles. The medical field has its humble roots in the extraction of beneficial compounds from medicinal plants. We learn from nature.

I left secondary education to go back to the lab because I felt I had more questions to ask of nature. I look at my work through a variety of lenses and parallels. My work parallels my philosophy. My work parallels my art, photography. In my art, a lens receives reflected energy, light, from a subject and focuses it on a digital sensor. Following the conversion of that light into a series of ones and zeroes, that information is fed to a computer, which converts data back to light on a monitor, producing an image. I find some of those images beautiful. Of course, I acknowledge my bias.

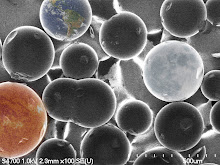

I left secondary education to go back to the lab because I felt I had more questions to ask of nature. I look at my work through a variety of lenses and parallels. My work parallels my philosophy. My work parallels my art, photography. In my art, a lens receives reflected energy, light, from a subject and focuses it on a digital sensor. Following the conversion of that light into a series of ones and zeroes, that information is fed to a computer, which converts data back to light on a monitor, producing an image. I find some of those images beautiful. Of course, I acknowledge my bias. In my science, I frequently place a sample of matter (a subject) I've created (sub-created, manipulated or synthesized might be more appropriate terms) in an instrument that bombards the matter with various radiation - ultraviolet, visible light, infrared, a beam of electrons - energy. The energy interacts with the sample and is either absorbed, reflected, scattered, and the energy emerging from the sample invariably reaches a digital sensor, undergoes a conversion by a computer to ones and zeroes, and, in the end, generally is rendered as an image. Some of these are more or less beautiful. Admittedly, it is difficult to admire the beauty of a ultraviolet-visible spectrum of a sample of silver nanoparticles. However, as noted in a previous post, these nanoscale objects possess a beauty that we can unlock with more sophisticated tools and methods.

In my science, I frequently place a sample of matter (a subject) I've created (sub-created, manipulated or synthesized might be more appropriate terms) in an instrument that bombards the matter with various radiation - ultraviolet, visible light, infrared, a beam of electrons - energy. The energy interacts with the sample and is either absorbed, reflected, scattered, and the energy emerging from the sample invariably reaches a digital sensor, undergoes a conversion by a computer to ones and zeroes, and, in the end, generally is rendered as an image. Some of these are more or less beautiful. Admittedly, it is difficult to admire the beauty of a ultraviolet-visible spectrum of a sample of silver nanoparticles. However, as noted in a previous post, these nanoscale objects possess a beauty that we can unlock with more sophisticated tools and methods.As I said, the notion of learning from the universe, earth, nature resonates with both scientific and mystic centers of my brain. At this point, after the discussion of nanoparticles and spectra, you may be thinking, "That's a stretch, Sandrik. Your nanoparticles aren't natural." Fair enough, but I disagree. In recent years the distinction between man-made and natural has given my brain some trouble. Certainly, I concede that there are sub-creations of humanity that are destructive by nature, even to ourselves. However, when a robin constructs a nest, do we call it robin-made? Do we distinguish it from what is natural? If a human builds a home of timbers from the forest, is it natural? If a steel doorknob is added? If vinyl siding is added? Where do we draw the line between the natural and the unnatural? Are humans natural? I think the last question gets more to the point. Was not all the matter in humans and the home present since the earth first cooled from a cloud of gas to a molten lump to a rocky orb covered mostly with water? If anything, we are manipulators, reassemblers, sub-creators, not makers. There can be no man-made, in the fundamental sense. To me, man-made implies a certain level of arrogance.

Björk relates this idea rather well in her song "The Modern Things."

All the modern thingsFurther, I think the natural/synthetic distinction serves to divorce and isolate us from the natural world. We see ourselves as a species apart from, rather than a species, a part of the natural world, much as our egos serve to isolate us from one another.

like cars and such

have always existed.

They've just been waiting in a mountain

for the right moment,

Listening to the irritating noises

of dinosaurs

and people

dabbling outside.

What's the point? Does the identification of ourselves and our sub-creations as natural give us license to run roughshod and re-create nature in our likeness? I wouldn't make that argument. While I wouldn't argue that my synthesis of nanoparticles is an unnatural process, any more so than is the construction of a robin's nest, I would and have argued that a kinship with nature should guide the manner in which I use, produce, spread and commercialize these nanoparticles. I believe the old model of holding dominion over the grass, herbs, fruit trees, great whales, winged fowls, cattle, creeping things, beasts of the earth has gotten us where we are today, with deteriorating air to breathe, water to drink, along with diminished diversity of living species with which to commune in the enjoyment of life.

So what, then? Is the pattern of heaven written on these nanoparticles? Probably not. But, when I watch the beaker of clear liquid turn yellow, and imagine the interplay of atoms, molecules and electrons, and observe a correspondence between that hump in the UV-Vis spectrum and the size and shape of the nanoparticles, viewing this whole process of nanoparticle synthesis and analysis in my mind's eye, from the macrocosm to the nanocosm, seeing the parts and the whole, all the while realizing that this process is but one character (in the language sense) in the script in this particular scene and act of the play that is the life of the universe, I experience what I can only describe as Zen, or enlightenment, or the touch of the Holy Spirit. The ego dissolves and I inhale and exhale in unison with the heaving cosmos. It feels similar to the solitude on the top of a mountain, or standing in the spray at the base of a waterfall. It's unity. It's a recognition of myself taking part in the life of the universe, and recognition of the life of the universe taking part in me.

I ask my questions. The universe answers.